Index for Activity Planning Toolkit

Click teal headings to move to that section

Accredited Continuing Education

Supported Activity Types & Descriptions

Currently Supported Credit Types by Discipline

Benefits of Interprofessional Collaborative Education (IPCE)

Educational Best Practices for IPCE

Interprofessional Collaborative Competencies & Characteristics

Learning Pyramid- Strategies for Sustainable Learning

SHINES: Sutter Health Informing Nurse Educators Series of Education Essentials

About Maintenance of Certification (MOCs)

Methods of Outcome Measurement

SDOH & Impact of Implicit Biases

Implementation Science Application to CPD, Performance Improvement, & Practice Change

Continuing Professional Development Policies

Essentials & Scope of Services

- Accredited Continuing Education is education that meets criteria and standards set by accrediting bodies (i.e., Joint Accreditation, BRN, ACCME, ANCC, ACPE etc.) for the purposes of continuing professional development of licensed professionals as well as maintenance of licensure, specialty certification & hospital privileges.

- Primary Criterion: The education demonstrates an “educational need” based on a “professional practice gap”.

- Definition of Educational Need: Need for education on a specific topic related to a gap in professional practice, often assessed through a Needs Assessment.

- Definition of a Practice Gap: The definition of a practice gap is an adaptation of the definition from the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality (AHRQ): “The difference between health care processes or outcomes observed in practice, and those potentially achievable on the basis of current professional evidence.”

- Educational design must address the educational needs (knowledge, skills/ strategies, or performance) that underlies the practice gaps of the healthcare team and/or the individual members of the healthcare team (JAC 4).

- Educational interventions should be designed to change the competence (skills/ strategies) or performance of the healthcare team and/or patient outcomes (JAC 5).

- Accredited continuing education has evolved to include:

- “Active learning strategies

- Incorporation of theory and evidence from the learning sciences

- Emphasis on educational activities based on data-defined gaps in care delivery

- Post-educational assessments of physician intent or commitment to change

- Emphasizing outcomes of care in addition to changes in knowledge”

- Source: Price, Davis & Filerman, 2021

- CPD Services Offered

- Coaching & Consultation-

- Design strategies aligned with healthcare education best practices

- Development of IPCE Champions to facilitate increased IPCE offerings

- CE/IPCE Review and Approval-

- Application and supporting documentation reviewed against JA criteria

- Quality rating for determination of minimum threshold for CE approval vs. exemplar

- Assessment & Mitigation of Commercial Bias or COIs- Financial Disclosure review, determination of conflict relevancy, facilitation of Peer Reviews and data warehousing

- Per Standards for Integrity & Independence in Accredited Continuing Education

- Streamlined Learner Services-

- Automation of direct reporting for physicians and pharmacists, alleviating the need for CME or CPE certificate management

- Automation of attendance tracking through SMS text messaging

- Provision of specialty credits such as Maintenance of Certification (MOCs)

- Quality Control-

- Adherence to JA & BRN accreditation criteria as well as regulatory requirements (i.e., AB 241 & 1195) relevant to continuing education

- Annual reporting as well as self-study for reaccreditation preparation

- Alignment with Sutter Health strategic initiatives

- Evaluating Educational Outcomes-

- Data collection and measurement of learner outcomes designed to improve, AT MINIMUM, learner competency

- Design strategies for higher level outcomes such as individual vs. team performance, patient outcomes, and/or population health status outcomes.

- Coaching & Consultation-

- Learning Objectives

- Objectives describe what the learner should be able to accomplish after completion of the activity. They must be specific, measurable actions that bridge the gap between the identified need/ gap and the desired best practice. Objectives are ideally written in three sections:

- Action Verb (stated in terms of performance objectives)

- Condition (the situation in which the learner might encounter this issue or problem)

- Standard (against which MEASURABLE success can be determined)

- Alternatively, you can write objectives using the Kern and Thomas Approach described in ACCME’s Tips for Writing Learning Objectives in the attachments below OR the SMART objectives approach described in the SHINES series (see link below).

- AVOID non-specific and unmeasurable terms such as:

- Appreciate

- Approach

- Be aware

- Be familiar with

- Become

- Believe

- Comprehend

- Conceptualize

- Experience

- Explore

- Grasp the significance of

- Grow

- Improve

- Increase

- Know

- Learn

- Think critically

- Understand

- Objectives describe what the learner should be able to accomplish after completion of the activity. They must be specific, measurable actions that bridge the gap between the identified need/ gap and the desired best practice. Objectives are ideally written in three sections:

- Taxonomies for Outcome Measurement

- Moore’s Taxonomy for Healthcare Education:

- The taxonomy that the ACCME relies upon as it was designed specifically for healthcare education and continuing professional development of healthcare professionals. It shows that the educational intervention is EFFECTIVE.

- Minimum threshold for approval is a Level 4 (Improved Competence) on Moore’s Taxonomy of Outcome Measures for Healthcare Education.

- Level 4: This is the degree to which a participant shows, in an educational setting, how to do what the CE/CME activity intended them to be able to do.

- Objective measurement thru observation in an educational setting

- Subjective measurement though a self-report of confidence in one’s competence, intention/commitment to change

- Moore’s Taxonomy for Healthcare Education:

- Bloom’s Taxonomy:

- Is a hierarchical classification of the different levels of thinking that should be applied when creating course objectives.

- Source: https://bloomstaxonomy.net/

- Bloom’s Taxonomy:

- Quality & Independence

- Sutter Health Assurance of Quality (SHAEQ) rubric

- Internally created rubric to identify the minimum threshold for activity approval, threshold for inclusion on CME Passport (for advertising to external learners), and threshold to be considered “exemplary” or “best practices” for system-wide learning. Quality categories include:

- Reason for training

- Evidence-Based Best Practice (EBP)

- Learning objectives

- Educational design

- Interprofessional Collaborative Education

- Enabling and reinforcing strategies

- Measured outcomes

- Additional considerations include whether a similar course already exists in the system, how the course supports Sutter Health strategic initiatives (e.g., is it aligned with Sutter Safe Care, Joy of Work, Workplace Violence Prevention, or other system-wide educational initiatives), and how does the course support both affordability (through a ROI) and achievement of learning objectives?

- Internally created rubric to identify the minimum threshold for activity approval, threshold for inclusion on CME Passport (for advertising to external learners), and threshold to be considered “exemplary” or “best practices” for system-wide learning. Quality categories include:

- Standards for Integrity & Independence in Accredited Continuing Education

- All recommendations for patient care in accredited continuing education must be based on current science, evidence, and clinical reasoning, while giving a fair and balanced view of diagnostic and therapeutic options.

- All scientific research referred to, reported, or used in accredited education in support or justification of a patient care recommendation must conform to the generally accepted standards of experimental design, data collection, analysis, and interpretation.

- Although accredited continuing education is an appropriate place to discuss, debate, and explore new and evolving topics, these areas need to be clearly identified as such within the program and individual presentations. It is the responsibility of accredited providers to facilitate engagement with these topics without advocating for, or promoting, practices that are not, or not yet, adequately based on current science, evidence, and clinical reasoning.

- Content cannot be included in accredited education if it advocates for unscientific approaches to diagnosis or therapy, or if the education promotes recommendations, treatment, or manners of practicing healthcare that are determined to have risks or dangers that outweigh the benefits or are known to be ineffective in the treatment of patients.

- Sutter Health Assurance of Quality (SHAEQ) rubric

- Supported Activity Types & Descriptions

- Live Courses including in-person, virtual, cohort, conference etc.

- An activity that occurs at a specific time (synchronous learning) as scheduled by the accredited continuing education provider. Participation may be in person, including multi-day events such as a training program with a series of unique sessions or conferences, or remotely as is the case of teleconference or live internet webinars.

- Regularly Scheduled Series

- A series of multiple, ongoing sessions, planned and presented to the organization’s professional staff following consistency in formatting, timing, and with unifying learning objectives (e.g., Grand Rounds, Tumor Boards, Case Conferences).

- Enduring Material otherwise known as on-demand or asynchronous learning

- An activity that ensures over a specified period of time and does not have a specific time or location designated for participation, rather the participant determines whether and when to complete the activity.

- Journal- Based otherwise known as journal clubs

- An activity that is planned and presented by an accredited continuing education provider and in which the learners read one or more articles from peer-reviewed, professional journals and then discuss application to practice.

- Performance Improvement including quality improvement or research-based

- An activity structured as a three-stage process by which a clinician or group of clinicians learn about specific performance measures, assess their practice using the selected performance measures, implement interventions to improve performance related to these measures over a useful interval of time, and then reassess their practice using the same performance measures. Completion of all three stages is approved for 20 hours of continuing education credit.

- Live Courses including in-person, virtual, cohort, conference etc.

- (Currently) Supported Credit Types by Discipline

- Physicians- ACCME via Joint Accreditation

- Nurses- CA BRN or ANCC and/or AMA PRA Category 1 CreditsTM hours for non-physicians via Joint Accreditation

- Pharmacists- ACPE via Joint Accreditation

- Social Workers- ASWB via Joint Accreditation

- Physical Therapist- PTBC via Joint Accreditation

- Other Healthcare Professionals- All other disciplines that accept AMA PRA Category 1 CreditsTM (e.g., Physician Assistants, Psychologists, and Respiratory Care Practitioners)

- Please Note: Our team is interested in building EQUITY in the support of continuing professional development for the interprofessional team so please let us know if you would like us to look into an accreditation that we do not already carry.

Activity Submission Process

- 1st Step (OPTIONAL): CPD Consultation Request @ SHSO.CPD@sutterhealth.org

- 2nd Step: Consider who should be involved.

- IPCE: For activities which target more than one discipline, (Interprofessional Continuing Education) you must have an integrated planning process that includes health care professionals who are reflective of the target audience members the activity is designed to address.

- Your team is not required to utilize the IPCE model for review and approval by CPD; however, our Executive leadership has given the directive that all planners of single-discipline activities must explain their rationale for why the educational activity is not interdisciplinary. IPCE is an evidence-based strategy to promote OPTIMAL patient and team outcomes in healthcare. For more information, please see our ABOUT page.

- PFAs: It is strongly recommended that patient or family advisors also be engaged as planners or teachers in the Interprofessional Continuing Education.

- According to the Theory of Dyadic Illness Management (Lyons & Lee, 2018), The family has an immediate and enduring impact on the patient’s health choices and acceptance of medical recommendations. Programs that aim to positively affect the patient should have a similar aim with regards to the family.

- IPCE: For activities which target more than one discipline, (Interprofessional Continuing Education) you must have an integrated planning process that includes health care professionals who are reflective of the target audience members the activity is designed to address.

- 3rd Step: Submit Preliminary Intake Form to CPD- See attachments below

- 4th Step: Financial Disclosures, Conflicts of Interest, & Commercial Support

- Instructions: All planners, faculty, moderators, or other individuals who have influence or control of the educational content of an accredited activity must disclose ALL financial relationships with any ineligible company within the past 24 months. This must occur early in planning for an accredited activity, as any ineligible relationships must be mitigated, or the individual must be recused, PRIOR to assuming a role with the accredited activity.

- Eligible vs. Ineligible Relationships: Examples of eligible and ineligible relationships include, but are not limited to, the following:

- Eligible:

- Ambulatory procedure centers

- Blood blanks

- Diagnostic labs that do not sell proprietary products

- Government of military agencies

- Group medical practices

- Health law firms

- Health profession membership organizations

- Hospitals and healthcare delivery systems

- Infusion centers

- Insurance or managed care companies

- Non-profit organizations

- Nursing homes or skilled nursing facilities

- Publishing or education companies

- Rehabilitation centers

- Schools of medicine or health science universities

- Software or game developers

- Ineligible:

- Advertising, marketing, or communication firms whose clients are ineligible companies

- Bio-medical start-ups that have begun a governmental or regulatory approval process

- Compounding pharmacies that manufacture proprietary compounds

- Diagnostic labs that sell proprietary products

- Growers, distributers, manufactured, or sellers of medical foods and dietary supplements

- Manufacturers of health-related wearable products

- Pharmaceutical companies or distributers

- Pharmacy benefit managers

- Reagent manufacturers or sellers

- Eligible:

- Unmitigable Relationships: The owners and employees of ineligible companies are considered to have unresolvable financial relationships and must be excluded from participating as planners or faculty and must not be allowed to influence or control any aspect of the planning, delivery, or evaluation of accredited continuing education, except in the limited circumstances outlined in Standard 3.2.

- Commercial Support: If commercial support is received for an activity there are certain regulatory requirements governing the location of vendors and timing intervals between vendor presentations and accredited CE content for both in-person and virtual events. Please discuss the specifics of your situation with the CPD department.

- 5th Step: Supporting Documentation

- Evidence-Based Practice References: Evidence-based references are required that support the educational need(s), including those identifying practice gaps or best practices for all activities. Additionally, for any clinical content that is focused on patient care there must be at least one reference that identifies applicable social determinants of health (SDOH) or strategies to address the SDOH to meet the requirements of AB 1195 on cultural and linguistic competencies as well as one reference that identifies the impact of clinician implicit biases as it relates to the content of the activity to meet the requirements of AB 241. Therefore, at minimum, activities will require the following level of support:

- Clinically Focused Activity Content:

- One reference supporting the professional practice gap. This can be from a peer-reviewed journal article as it applies to observed practice gaps in other similar healthcare organizations OR from internal data showing a professional practice gap specific to Sutter Health.

- Two references supporting the evidence-based best practices, guidelines, or interventions to mitigate the practice gap.

- One reference related to the Social Determinants of Health relevant to the topic. More information can be found on this in the section below.

- One reference related to the Implicit Bias Considerations relevant to the topic. More information can be found on this in the section on Social Determinants of Health and Implicit Biases below.

- Non-Clinically Focused Activity Content:

- One reference supporting the professional practice gap. This can be from a peer-reviewed journal article as it applies to observed practice gaps in other similar healthcare organizations OR from internal data showing a professional practice gap specific to Sutter Health.

- Two references supporting the evidence-based best practices, guidelines, or interventions to mitigate the practice gap.

- Clinically Focused Activity Content:

- Timed Agendas: Supporting documentation of instructional minutes must be provided for appropriate credit calculation. This includes indication of START TIME and DURATION as well as the nature of each component (e.g., didactic lecture, interactive Q & A, simulation, return-demonstration of a learned skill etc.) Credit calculation does NOT include welcome or closing remarks, housekeeping messages or other announcements, breaks, meals, networking opportunities or other social activity, graduation ceremonies etc. It is also important to note that various disciplines have different rules for credit calculation so at times your team may be asked to modify your timed agenda to better promote equity in credit calculation for all disciplines in attendance.

- Other Requirements if Applicable

- Evaluation Options: The CPD department offers a Sutter standardized evaluation that meets the minimum threshold for subjective assessment of a Level 4 Outcome on the Moore’s Taxonomy of Healthcare Education Outcomes. Your team is not required to use the evaluation; however, all activities must have an immediate post-activity evaluation that demonstrates at least a Level 4 outcome.

- Explanation of Commendation Criteria: The Joint Accreditation Commendation criteria represents educational best practices for healthcare education. They are not required for individual activities; however, our continuing professional development program as a whole must demonstrate that several activities do reflect these commendation criteria and that we are striving to meet all of the commendation criteria somewhere in our portfolio. Therefore, all teams are strongly encouraged to consider how they might build commendation criteria into their planning and design of educational activities.

- Follow-up Surveys: In addition to the immediate post-activity evaluation that is REQUIRED, teams are strongly encouraged to consider the use of follow-up survey at least 2 months after an educational activity has occurred to assess self-reported adherence to guidelines or recommendations. It is also strongly recommended that you ask learner what, if any, implementation barriers they have encountered to utilizing what they had learned in the activity. This information can then be used to revise existing content to address those specific implementation barriers or to identify what other interventions (e.g., policy or resources) must be provided in order for the learners to be successful in application of what they have learned.

- Marketing Materials: All marketing materials must be submitted to the CPD department to review in accordance with regulatory requirements and internal policies. There are a few very important accreditation requirements to be aware of that relate to marketing or program materials:

- “Accredited CME providers are required to have two statements on their promotional materials, one of which will state the source of their accreditation (e.g., ACCME via JA). The other is the AMA Credit Designation Statement, which states the maximum number of AMA PRA Category 1 Credits™ for which the activity has been certified.” This means that an activity cannot be promoted to learners as an accredited continuing education activity until it has, in fact, been fully certified or approved, by the CPD Provider Designee/Verifier.

- To help learners “identify legitimate AMA PRA Category 1 Credit™ activities, the AMA requires accredited CME providers to trademark the credit phrase (“AMA PRA Category 1 Credit™”)” and follow very specific wording. “Variations or parts of the credit designation phrase must never be used” and learners are encouraged to question the legitimacy of educational activities that do not follow appropriate formatting.

- “The AMA credit designation statement must be used in both activity announcements and any program materials, in both print and electronic formats (e.g., a course syllabus, enduring material publication, landing page of an internet activity), that reference CME credit, and any document that references the number of credits for which the activity has been designated.”

- “Save the Date” announcements that do not state the number of credits expected are allowed in advance of approval; however, such announcements “may never indicate that “AMA PRA Category 1 Credit™ has been applied for,” is pending, or any similar wording.”

- Source: American Medical Association, CME Provider FAQ, 2019

- Presentation Materials: Submission of all presentation materials is expected for the purposes of:

- Assessing for and mitigating conflicts of interest, commercial bias, educational content that is not supported by peer-reviewed evidence, and/or “emerging evidence” that is not clearly labeled as such in the presentation materials in accordance with the Standards for Integrity and Independence in Accredited Continuing Education.

- Confirmation of application of educational best practices in accordance with Joint Accreditation criteria.

- Maintenance of complete educational files for the purposes of audits or reaccreditation.

- Evidence-Based Practice References: Evidence-based references are required that support the educational need(s), including those identifying practice gaps or best practices for all activities. Additionally, for any clinical content that is focused on patient care there must be at least one reference that identifies applicable social determinants of health (SDOH) or strategies to address the SDOH to meet the requirements of AB 1195 on cultural and linguistic competencies as well as one reference that identifies the impact of clinician implicit biases as it relates to the content of the activity to meet the requirements of AB 241. Therefore, at minimum, activities will require the following level of support:

Educational Best Practices & Adult Learning Theories

- Benefits of Interprofessional Collaborative Education (IPCE): Interprofessional continuing education (IPCE) is when members from two or more professions learn FROM, WITH & ABOUT each other to enable effective collaboration and improve health outcomes (AACME, ACPE, ANCC, 2015). Not only does IPCE support quality improvement initiatives as outlined by the National Academies of Medicine and the World Health Organization, but it is also a strong facilitator of many internal Sutter Health strategic initiatives. Benefits include:

- Enhancing collaborative practice & improved team communication- Failures in communication are consistently one of the top three root causes of sentinel events. The Institute of Medicine (IOM) has a series of reports demonstrating the relationship between poor team performance and negative patient outcomes and recommends implementation of IPCE as a solution.

- Facilitating interprofessional redesign of complex systems of care- Most healthcare is delivered by teams, thus the IOM recommends moving education away from a model that focuses solely on individual responsibilities towards a model that integrates the role of teams to ensure that the care is continuous and reliable. This is in-line with Sutter Health’s drive to become a High Reliability Organization.

- Improving both patient and system outcomes- The World Health Organization issued a framework for action, describing the imperative for education that develops collaborative practice with healthcare professionals working together with patients and families to deliver the highest quality of care.

- Reducing individual workloads & increasing job satisfaction- Every health profession has its own subculture, knowledge base, and perceived power hierarchy which leads to some members’ voices being prioritized over others & poor staff morale. IPCE has been shown to increase awareness of the expertise of other professions, create a sense of partnership, and improve staff retention as well as recruitment.

- Educational Best Practices for IPCE: Whenever possible IPCE interventions should include the following:

- Grounding in Purpose:

- Explain WHY the education is important. Consider starting with a story or patient testimonial and then identify shared goals/ learning objectives with the learners.

- Identify student’s motivation to be involved in the learning, what they expect to achieve, & baseline knowledge. (Consider doing this at the time of registration if possible.)

- Articulate level of commitment involved (including any post-activity evaluations, surveys, or follow-ups), indications of success/ competencies, and value of the education.

- Collaborative Planning & Participation:

- Many, or all, members of the interprofessional team are afforded opportunities to learn from and with each other (e.g., nurses, physicians, advanced practice clinicians, pharmacists, case managers, social workers, chaplains, dieticians, child-life specialists, administrators, risk management analysts, informatics specialists, students, volunteers, former patients etc.) as educational intervention planners or participants.

- Goal- 90% of IPCE will have a patient/ family advisor as part of the planning team or faculty.

- Value- IPCE experiences provide optimization of interdisciplinary interaction, enhanced team building activities, and development of collaborative competencies.

- Interactive & Multi-Faceted Educational Strategies:

- Use of engaging or immersive active learning strategies such as:

- Case Studies

- Think-Pair-Share Activities

- Flipped Classroom Approach

- Small-Group Discussions and/or Peer Instruction

- Simulation (e.g., for technical skills or critical thinking in a team environment)

- Script Concordance Testing for Competency Assessment

- Reflection and/or One Minute Recap

- And more…

- Case Studies in particular, when used alone or integrated into simulation, are well-supported as ideal tools for teaching complex clinical concepts. Learners can explore multi-faceted, reality-based situations in the context of team-building problem-solving, critical thinking, and the application of knowledge.

- These strategies can be integrated into a variety of educational activity types including Regularly Scheduled Series (RSS), Live Courses (Virtual or In-person), Performance Improvement, and Enduring Material (Virtual).

- Use of engaging or immersive active learning strategies such as:

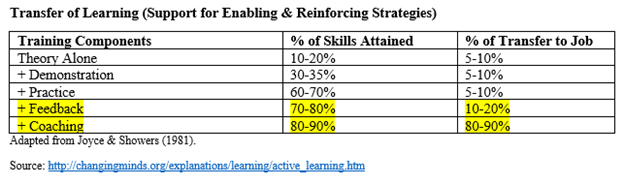

- Enabling or Reinforcing Interventions: The most effective educational strategies, in terms of clinician behavior change, pair knowledge transmission with enabling or reinforcing interventions including:

- Individualized feedback

- Sequential & progressive education sessions (with repetition of key content)

- Written educational material/ posters in common spaces and/or documentation reminders

- Implementation strategies focused on specific barriers or needs

- Follow-up meetings to discuss challenging cases

- 1:1 Coaching

- Grounding in Purpose:

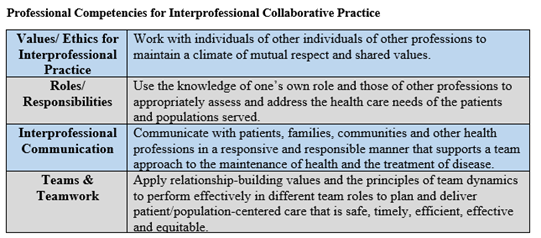

- Interprofessional Collaborative Competencies & Characteristics: Characteristics of an effective team include:

- Clarity in one’s role & the role of others

- Confidence, trust & mutual respect in relation to team members

- Clear Communication with awareness of discipline-specific cultural differences

- Coordination of activities & the ability to overcome challenges

- Compassionate awareness of personal differences

- Collective leadership

- Source: Interprofessional Education Collaborative Expert Panel, 2011.

- Learning Pyramid- Why do we need active learning as well as enabling and reinforcing strategies for sustainable education?

- Key Takeaway: There is a need to “deeply process” content for sustainable learning. “Deeply processing the content promotes changes to memory, which is needed to learn, remember & apply. The mental activity used in deep processing is what leads to learning (whether it is passive or active). This helps the learner move from simply knowing to the ability to use.” –Patty Shank, PhD

- Promote deep processing by having learners restate the material in their own words, organize content to show relation, ask “when should we…”, analyze which principles apply, use resources/ tools & solve relevant problems.

- SHINES: Sutter Health Informing Nurse Educators Series of education essentials: This is a series designed to help newer educators or educators who lack any formal training in educational pedagogy from a university degree or graduate program to explore the “essentials” of educational design, delivery, and outcome analysis. 2022 Sessions Include:

- Engaging Adult Learners: Fundamentals of Teaching and Learning

- Conducing a Needs Assessment: Is Education the Right Intervention?

- Identifying Required Education (in Healthcare)

- Creating Fun and Memorable Immersive Educational Experiences

- Objectives, Outcomes & Evaluation

- Continuing Education: Meeting Accreditation Requirements

- Theories of Adult Learning: Some common barriers to adult learning include limited amount of time, contradiction in educational content (even within one organization with silos of educational content development), lack of perceived support, and lack of application of appropriate adult learning theories. Below are some of the major adult learning theories as compiled by Western Governors University: https://www.wgu.edu/blog/adult-learning-theories-principles2004.html#close

- Andragogy: “Malcom Knowles popularized the concept of andragogy in 1980. Andragogy is the “art and science of helping adults learn” and Malcolm Knowles contrasted it with pedagogy, which is the art and science of helping children learn. Knowles and the andragogy theory state that adult learners are different from children in many ways, including:

- They need to know why they should learn something

- They need internal motivation

- They want to know how learning will help them specifically

- They bring prior knowledge and experience that form a foundation for their learning

- They are self-directed and want to take charge of their learning journey

- They fond the most relevance from task-oriented or application-based learning that aligns with their own realities (or practice settings in healthcare)

- Andragogy learning theories focus on giving students an understanding of why they are doing something, lots of hands-on experiences, and less instruction so they can tackle things themselves. The andragogy adult learning theory isn’t without criticism—some suggest that the andragogy adult learning theory doesn’t take other cultures into consideration well enough. While there are pros and cons, many students find andragogy is extremely accurate and helpful as they work to continue their education and learning.”

- Transformative Learning: “Jack Mezirow developed this learning theory in the 1970’s. The transformative adult learning theory (sometimes called transformational learning) is focused on changing the way learners think about the world around them, and how they think about themselves.

- Sometimes transformative learning utilizes dilemmas and situations to challenge your assumptions and principles. Learners then use critical thinking and questioning to evaluate their underlying beliefs and assumptions and learn from what they realize about themselves in the process. Mezirow saw transformative learning as a rational process, where learners challenge and discuss to expand their understanding. “

- Transformative Learning approaches are considered ideal to address cultural implementation barriers to evidence-based best practices; however, critics note that it is important for educators to promote psychologically safe learning environments where learners can feel safe to share their thoughts, feelings, and beliefs without fear of criticism or punitive action.

- Self-Directed Learning: “Self-directed learning is an interesting adult learning theory that has been around for hundreds of years. It became a more formal theory in the 1970’s with Alan Tough and is used by teachers in a variety of educational settings to help improve adult learning. Self-directed learning (sometimes called self-direction learning) is the process where individuals take initiative in their learning—they plan, carry out, and evaluate their learning experiences without the help of others. Learners set goals, determine their educational or training needs, implement a plan, and more to enhance their own learning. Self-directed learning may happen outside the classroom or inside of it, with students working by themselves or collaborating as part of their self-directed learning process.

- Criticism for this self-directed approach comes from those who say that some adult learners lack the confidence and understanding to do self-directed learning well. Critics also say that not all adults want to pursue self-directed learning.”

- Experiential Learning: “David Kolb championed this theory in the 1970’s, drawing on the work of other psychologists and theorists. Experiential learning theory focuses on the idea that adults are shaped by their experiences, and that the best learning comes from making sense of your experiences. Instead of memorizing facts and figures, experiential learning is a more hands-on and reflective learning style. Adult learners are able to utilize this theory and learn by doing, instead of just hearing or reading about something. Role-play, hands on experiences, and more are all part of experiential learning.”

- Project-Based Learning: “As early as 1900, John Dewey supported a “learning by doing” method of education. Project-based learning (sometimes called problem-based learning) is similar to experiential and action learning in that the overall idea is to actually do something to help you learn, instead of reading or hearing about it. Project-based learning utilizes real-world scenarios and creates projects for learner that they could apply on the job in the future.

- The major criticism of project-based learning is that the outcomes aren’t proven. There isn’t enough evidence to show that project-based learning is as effective as other learning methods.”

- Andragogy: “Malcom Knowles popularized the concept of andragogy in 1980. Andragogy is the “art and science of helping adults learn” and Malcolm Knowles contrasted it with pedagogy, which is the art and science of helping children learn. Knowles and the andragogy theory state that adult learners are different from children in many ways, including:

Maintenance of Certification (MOCs)

- About Maintenance of Certification: Maintenance of Certification (MOC), also known as Continuing or Continuous Certification, is the process by which a physician who has initially become board certified in the specialty practice of their choice maintains their board certification status. Accredited CME activities may be registered for MOC credit for Part II: Lifelong Learning and/or Self-Assessment and Part IV: Improvement in Medical Practice provided the activity meets the requirements for various MOC boards and is not an excluded activity type for that board (e.g., American Board of Pediatrics does not allow Performance Improvement CME to count for MOC). Some boards have a requirement to engage in education related to patient safety issues, and those boards allow accredited CME activities to be registered for Patient Safety credit.

- Core Competencies- The American Board of Medical Specialties (ABMS) Program for MOC involves ongoing measurement of six core competencies defined by ABMS and the Accreditation Council for Graduate Medical Education (ACGME) which include:

- Practice-Based Learning and Improvement

- Patient Care & Procedural Skills

- Systems-Based Practice

- Medical Knowledge

- Interpersonal & Communication Skills

- Professionalism

- General Requirements- Accredited CME providers must do all of the following:

- Attest to compliance with certifying board requirements

- Agree to collect the required individual learner completion data, including participation verification as well as evaluation and feedback mechanisms, and submit it via PARS

- Agree to abide by certifying board and ACCME requirements for use of the data

- Agree to allow ACCME to publish data about the activity on ACCME’s website (www.cmepassport.org), if applicable

- Agree to comply with requests for information about the activity if the activity is selected for an audit by ACCME

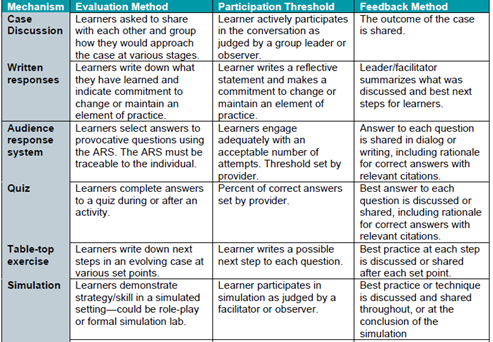

- Participation Threshold, Evaluation, & Feedback Examples- Participating certifying boards and ACCME share the expectation that accredited providers evaluate the impact of their activities on learners’ competence, performance, or patient outcomes. The following examples of evaluation approaches have been compiled as a resource for accredited providers. These are only examples—and not an exhaustive list—of the methods that can be used by the accredited provider in CME that supports MOC. Some certifying boards may have evaluation requirements in addition to those provided in the table below.

- Core Competencies- The American Board of Medical Specialties (ABMS) Program for MOC involves ongoing measurement of six core competencies defined by ABMS and the Accreditation Council for Graduate Medical Education (ACGME) which include:

Methods of Outcome Measurement

The minimum threshold for activity approval is a (subjective) self-assessment of improved competence via the CPD standardized evaluation (or equivalent). Consistent with outcomes frameworks such as Moore’s Taxonomy, accredited continuing education providers should strive to prioritize facilitating sustained clinical behavior change as an outcome of healthcare education. It is important to note that an activity can be designed to improve patient outcomes; however, unless your team is measuring changes in the health of patients as a direct result of the educational intervention(s) then an activity cannot be said to have achieved this outcome. Below are a few examples or evaluation methods for each level of outcome.

- Level 4- Improved Competence/Skills/Strategy: Competence = Knowledge + Strategy to use the knowledge in practice. These evaluation mechanisms are attempting to answer- “Can learners apply what was learned to their work?”

- Post-Activity Evaluation that includes an assessment of learner’s commitment/intent to change- REQUIRED on ALL Activities

- Pre- and post-tests

- Case Study with in-class questions

- Audience Response System (ARS) or polling that can be traced to the individual

- Observation in an educational setting

- Level 5- Improved Individual or Team Performance: Performance = New skills/strategies adopted in practice. These evaluation mechanisms are attempting to answer- “Have learners implemented what was learned into interprofessional collaborative practice?”

- Self-reported adherence to guidelines ~2 months post-activity (via survey, interview, or focus group)

- Direct supervisor and/or patient feedback ~ 2 months post-activity

- Case-based follow-up discussions (which can be used as both performance evaluation as well as enabling & reinforcing mechanisms)

- Chart audits for clinician behavioral change (e.g., documentation, referral)

- Observation in a practice setting

- Level 6/7- Improved Patient and/or Population Outcomes: Improved Patient Outcomes = Substantial changes in the health conditions of patients. These evaluation mechanisms are attempting to answer- “Will learners implement what they learned in a way that improves outcomes?”

- Observed changes in health status measure recorded in patient charts or administrative database

- Patient self-reports of health status (via surveys/other documented feedback)

- Community surveys

- Epidemiological data/reports

- Analysis of QI/QA or research data collected before and after educational intervention

Options for Direct Reporting

- ACPE for Pharmacy: Our accreditation requires use of CPE Monitor for Pharmacists and Pharmacy Technician credit. CPE Monitor is a national, collaborative effort by ACPE and the National Association of Boards of Pharmacy (NABP) to provide an electronic system for pharmacists and pharmacy technicians to track their completed continuing pharmacy education (CPE) credits. It will also offer boards of pharmacy the opportunity to electronically authenticate the CPE units completed by their licensees, rather than requiring pharmacists and pharmacy technicians to submit their proof of completion statements (i.e., statements of credit) upon request or for random audits.

- How CPE Monitor Works: Pharmacists and pharmacy technicians will receive a unique identification number (ID) after setting up their NABP e-Profile and registering for CPE Monitor. ACPE-accredited providers will request pharmacist and pharmacy technician participants to provide their NABP e-Profile ID and date of birth (in MMDD format) when they register for a CPE activity or submit a request for credit. It will be the responsibility of the pharmacist or pharmacy technician to provide the correct information [i.e., ID and DOB (in MMDD format)] within 30 days of the activity in order to receive credit for participating in a CPE activity.

- ACPE’s Types of Continuing Pharmacy Education:

- Knowledge-Based CPE Activities- These CPE activities should be designed for participants to acquire factual information. Minimum credit: 0.25 contact hours or 15 minutes. Knowledge-based CPE activities begin at the Knowledge Level of Bloom’s taxonomy through to the Comprehension Level, encompassing the following verbs that should be used for developing performance objectives, learner assessments and learning tasks:

- Activity purpose is knowledge transfer. Learning assessments can be in the form of questions or recall of facts; however, feedback must be provided to all participants.

- Examples of Knowledge Tasks: Arrange, define, duplicate, label, list, memorize, name, order, recognize, relate, recall, repeat, reproduce, state.

- Examples of Comprehension Tasks: Classify, describe, discuss, explain, express, identify, indicate, locate, recognize, report, restate, review, select, translate.

- Application-Based CPE Activities- These CPE activities should be designed for participants to learn concepts and apply information during the activity. Minimum credit: 1.0 contact hour or 60 minutes. Although application-based CPE activities may include foundational knowledge, they are primarily intended to begin at the Application Level of Bloom’s taxonomy through to the Evaluation Level, encompassing the following verbs that should be used for developing performance objectives, learner assessments and learning tasks:

- Activity purpose if to application to practice. Learning assessments can be in the form of case studies or application of principles; however, feedback must be provided to all participants.

- Examples of Application Tasks: Apply, choose, demonstrate, dramatize, employ, illustrate, interpret, operate, practice, schedule, sketch, solve, use, write.

- Examples of Analysis Tasks: Analyze, appraise, calculate, categorize, compare, contrast, criticize, differentiate, discriminate, distinguish, examine, experiment, question, test.

- Examples of Synthesis Tasks: Arrange, assemble, collect, compose, construct, create, design, develop, formulate, manage, organize, plan, prepare, propose, set up, write.

- Examples of Evaluation Tasks: Appraise, argue, assess, attach, choose, compare, defend estimate, judge, predict, rate, core, select, support, value, evaluate.

- Certificate Program- Previously named Practice-Based CPE Activities- These CPE activities are primarily constructed to instill, expand, or enhance practice competencies through the systematic achievement of specified knowledge, skills, attitudes, and performance behaviors. The information within the certificate program must be based on evidence as accepted in the literature by the health care professions. The formats of these CPE activities should include a didactic component (live and/or home study) and a practice experience component (designed to evaluate the skill or application). The provider should employ an instructional design that is rationally sequenced, curricular based, and supportive of achievement of the stated professional competencies. Minimum credit: 15 contact hours. Practice-based CPE activities should include the upper levels of Bloom’s cognitive taxonomy but may also include lower levels for foundational knowledge. Because these activities emphasize the use of knowledge and skills in real-life practice, as well as the development of clinical-practice values, practice-based CPE activities should also be created using learning taxonomies for psychomotor skills and for attitudes.

- Activity purpose is to instill knowledge, skills, and attitudes necessary to sustain meaningful practice change. Learning assessments should be formative and summative; however, feedback must be provided to all participants.

- Knowledge-Based CPE Activities- These CPE activities should be designed for participants to acquire factual information. Minimum credit: 0.25 contact hours or 15 minutes. Knowledge-based CPE activities begin at the Knowledge Level of Bloom’s taxonomy through to the Comprehension Level, encompassing the following verbs that should be used for developing performance objectives, learner assessments and learning tasks:

- Medical Board of California for MDs: The ACCME and State Medical Licensing Boards Collaboration enables accredited CME providers to report CME activity completion data for physicians who hold a medical license in any state or territory in the United States. State Medical Boards that have joined the collaboration can log in to PARS, view and verify the CME credit data that has been reported by accredited CME providers for their licensees. Benefits include:

- Decrease physicians’ reporting burden “giving them more time to focus on high-quality learning and their patients, rather than paperwork” (ACCME, 2022).

- Reduce providers’ work responding to queries and certificate requests from physicians

- Support regulatory authorities by providing easier, online access to verified CME-completion data, thus reducing manual review of paper or scanned CME certificates

- Participating State Medical Boards:

- Alabama Board of Medical Examiners

- Medical Board of California

- Maine Board of Licensure in Medicine

- Maine Board of Osteopathic Licensure

- Maryland Board of Physicians

- North Carolina Medical Board

- North Dakota Board of Medicine

- Oregon Medical Board

- Virgin Islands Board of Medical Examiners

- Washington Medical Commission

- Source: https://accme.org/state-medical-licensing-boards-collaboration

- Responsibilities of Accredited CME Providers Participating in the Collaboration:

- Comply with ACCME accreditation requirements

- Obtain consent from licensees who participate in the activity to report their participation to the ACCME and the appropriate regulatory boards

- Grant the ACCME permission to share the specific data that is entered into PARS with the appropriate regulatory bodies.

- Obtain the month and day of birth, state of licensure and license number (or NPI) from any physician who has given permission to have their CME credit data reported in PARS.

- Compile and upload the CME credit data within 30 days of the activity using one of the methods below. Timely reporting is especially important since renewal cycles for physician licensees occur throughout the year and do not necessarily coincide with the end of the calendar year.

- Resolve any CME credit submission errors.

- Retain participation records for six years after the activity.

Social Determinates of Health (SDOH) & the Impact of Implicit Biases

- Social Determinates of Health: Social determinants of health are linked to a lack of opportunity & to a lack of resources to protect, improve, and maintain health. SDOH include, but are not limited to, the following:

- Health Services- Access to high-quality healthcare, health literacy, insurance status, & provider's linguistic competency and/or cultural humility.

- Social Environment- Adverse Childhood Experiences (ACEs), political ideologies, community engagement, culture, discrimination (including racism & gender inequality), social connection/ integration, social status, stressors/ coping skills for stress, & support systems.

- Economic- Employment & working conditions, expenses/ debts (including medical bills), & income disparities.

- Education- Higher education, literacy/ language, access to early childhood education & vocational training.

- Food Access- Access to healthy food options & hunger.

- Physical Environment- Built environment, crowded conditions, housing, safety, & transportation.

- California Legislation related to SDOH & the Impact of Implicit Biases

- California Assembly Bill 1195, which went into effect July 1, 2006, requires continuing medical education activities with patient care components to include cultural and linguistic curriculum. Additionally, considerations of impact on the LGBTQ+ community (if applicable to the topic) was added to the legislature in September 2014.

- California Assembly Bill 241, which went into effect January 1, 2022, requires all continuing education activities with patient care components intended for physicians, surgeons, physician assistants, nurses, or other healing arts licensees to include curriculum that includes specified instruction (relevant to the content) in the understanding of implicit bias in medical treatment. This legislation stipulates that healthcare licensees must be provided with “strategies for understanding and reducing the impact of their biases in order to reduce disparate outcomes and ensure that all patients receive fair treatment and quality health care.” (Legislature.ca.gov, 2021).

- The intent is for continuing education to address the cultural and linguistic concerns of diverse patient populations through appropriate professional development, cultural humility, and mitigation of implicit bias, including:

- Determine for each planned activity with a clinical care focus what are the cultural, linguistic and/or health disparities relevant to the targeted learners and/or their patient community.

- Determine the related implicit bias considerations for your content. Besides biases related to age, gender, and ethnic identity your team may also want to consider affinity bias, attribution bias, confirmation bias, conformity bias etc.

- Once a relevant cultural, linguistic and/or health disparity is identified, generate at least one educational component to address the specific need(s) related to the educational activity. Ensure that this also includes identification of implicit bias implications.

- Sutter Health Compliance Levels for Addressing the Impact of Implicit Biases

- Compliance Level I: Provide learners with resources for self-directed learning on cultural and linguistic considerations, as well as the impact of implicit bias, relevant to the content.

- Compliance Level II: Guide faculty/presenters to address relevant cultural issues and implicit bias considerations with at least one dedicated slide (or equivalent) in the presentation.

- Compliance Level III: Guide faculty/presenters to address relevant cultural issues and implicit bias considerations as an integrated component of the presentation.

- Compliance Level IV: Presentation includes active learning or deep reflection strategies designed to improve practice and/or behavioral change as it relates to providing culturally appropriate care which is free from the impact of implicit biases.

- Additional Resources:

- Agency for Healthcare Research & Quality: https://www.ahrq.gov/sdoh/index.html

- For more information on AB 1195- Coto- Continuing Education: Cultural & Linguistic Competency: https://leginfo.legislature.ca.gov/faces/billTextClient.xhtml?bill_id=200520060AB1195

- For more information on AB 241- Kamlager-Dove- Continuing Education: Implicit Bias Requirements: https://leginfo.legislature.ca.gov/faces/billNavClient.xhtml?bill_id=201920200AB241

Implementation Science

- How Implementation Science Applies to Continuing Education, Performance/Quality Improvement, and Practice Change Initiatives: Framework for an Implementation Science Approach to Accredited Continuing Education/Continuing Medical Education in Learning Health Enterprises (Source: National Academy of Medicine, Price, Davis & Filerman, 2021)

- “Implementation science is the study of methods to promote the adoption and integration of evidence-based practices and policies into routine health care and public health settings to improve population health. Implementation science uses theories, models, principles, research designs, and methods derived from multiple disciplines and industries outside of medicine (e.g., organizational development, quality improvement, industrial engineering, business management, social science). Partnerships with key stakeholder groups (e.g., patients, providers, organizations, health systems, or communities) are critical in the application of implementation science. Medical educators and health system leaders are increasingly turning to an implementation science lens to help frame and evaluate the impact of their work.

- Conceptual frameworks are used to develop and evaluate multifaceted interventions. Building upon previous research (often outside of medicine), these frameworks describe and explain concepts, assumptions, expectations, key factors, constructs, and variables that may influence an outcome of interest. The use of conceptual frameworks may increase the generalizability of findings. Below, the authors describe a framework derived from implementation science that can be used to conceptualize, design, implement, and evaluate CME (or accredited continuing education) integrated into health enterprise improvement.

- The Consolidated Framework for Implementation Research (CFIR): The Consolidated Framework for Implementation Research (CFIR) was developed to identify factors that might influence implementation and effectiveness of multifaceted interventions and guide rapid systematic assessment of such. It contains 39 constructs derived from several theories, including Rogers’s diffusion of innovation and Prochaska’s transtheoretical stages of change in five domains, most recently updated in Nov. 2022:

- Innovation Domain- Formerly Intervention Characteristics: Characteristics and components of the “thing” (e.g., practice change) being implemented

- Inner Setting Domain: Features of the implementing organization(s); the setting in which the innovation is being implemented

- Outer Setting Domain: Features of the external context or environment; the setting in which the Inner Setting exists

- Individuals Domain: Roles and characteristics of those Involved in the innovation implementation

- Implementation Process Domain: Strategies or tactics that might influence the effectiveness of sustainability of the innovation implementation

- During intervention design, CFIR can help proactively anticipate facilitators and barriers (e.g., complexity, cost, inertia, competing priorities) to implementation. It can help tailor intervention structure and delivery across individuals, settings, and levels within an organization. CFIR can also identify barriers and facilitators to implementation in real-time rapid-cycle evaluation and suggest intervention improvement to stakeholders and leaders [66]. Stakeholders and subject experts within a health care enterprise could collaborate in different aspects of planning and delivery of educational and improvement interventions. For example, subject matter experts and informaticists could be responsible for gathering information on the strength of evidence. CME (or accredited continuing education) professionals could be responsible for the development of targeted, interactive, reflective, longitudinal activities for individuals and interprofessional teams that address knowledge, beliefs, skills, and self-efficacy. The CFIR model can help CME leaders new to or already engaging in accredited interprofessional continuing education more visibly align with the needs of health enterprises and leaders. Quality improvement and operational leaders could be responsible for implementation. Data analysts and embedded organizational researchers could be responsible for mixed methods evaluation of efforts” (Price, Davis & Filerman, 2021).

- More on CFIR: The CFIR Framework “provides a menu of constructs that have been associated with effective implementation. It reflects the state-of-the-science; including constructs from, for example, Everett Rogers’ Diffusion of Innovations Theory and Greenhalgh and colleagues’ significant compilation of constructs based on their review of 500 published sources across 13 scientific disciplines. In addition to these two sources, the CFIR incorporates 18 other sources. The CFIR considered the spectrum of construct terminology and definitions and compiled them into one organizing framework.

- The CFIR framework provides validated questions addressing constructs arranged across 5 domains that can be used in a range of applications. It can provide a practical guide for systematically assessing potential barriers and facilitators in preparation for implementing an innovation, to providing theory-based constructs for developing context-specific logic models or generalizable middle-range theories.

- The CFIR was developed by implementation researchers affiliated with Veterans Affairs (VA) Diabetes Quality Enhancement Research Initiative (QUERI). The VA QUERI was launched in 1998 as part of a system-wide transformation aimed at improving the quality of healthcare for Veterans and continues to contribute to this effort by implementing research findings and innovations into routine clinical practice.

- Benefits of CFIR: Systematic analysis, organization of findings, and easily customized to diverse settings and scenarios.

- Source: https://cfirguide.org/

(Coming Soon) Continuing Professional Development Department Policies

- Advertising, Promotion, & Commercial Bias in Accredited Continuing Education

- Commercial Support Requirements in Accredited Continuing Education

- What is commercial support

- Commercial Support Guidelines: Allowable & Prohibited

- Disclosing Commercial Support to Learners

- Independence of Curriculum

- Identification, Resolution, & Disclosure of Conflicts of Interest in Accredited Continuing Education

- Review & Administration of Continuing Education

External Links & References

- ACCME’s CE Educator’s Toolkit: https://accme.org/sites/default/files/2022-04/CE%20Educator%27s%20Toolkit.pdf

- ACCME’s Tips for Writing Learning Objectives: https://www.facs.org/media/inlg4ibe/tips_for_writing_learning_objectives.pdf

- Bias and Racism Teaching Rounds at an Academic Medical Center. (Capers, Bond, & Nori, 2020). https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/32882252/

- CME and MOC “All Together Now”: https://www.abim.org/about/publications/shareables/all-together-now-earn-cme-moc-all-at-once

- CME for Maintenance of Certification (MOC) Activity Planning Worksheet: https://www.accme.org/publications/cme-for-moc-planning-guide

- Continuing Professional Development: Building and Sustaining a Quality Workforce. (National Academies Press, 2010): https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK219809/

- Cultural Humility Versus Cultural Competence: A Critical Distinction in Defining Physician Training Outcomes in Multicultural Education. (Tervalon & Murray-Garcia, 1998). https://melanietervalon.com/wp-content/uploads/2013/08/CulturalHumility_Tervalon-and-Murray-Garcia-Article.pdf

- IPEC Competency Self-Assessment Tool. (National Center for Interprofessional Practice and education, 2016): https://nexusipe.org/advancing/assessment-evaluation/ipec-competency-self-assessment-tool

- Recommendations for Case Study Design

- Recommendations for Case Study Learner Analysis

- Sutter Health Assurance of Educational Quality (SHAEQ)

- Sutter Health Medical Library

- “Systems-Integrated CME”: The Implementation and Outcomes Imperative for Continuing Medical Education in the Learning Health Care Enterprise. (National Academy of Medicine, Price, Davis & Filerman, 2021): https://nam.edu/systems-integrated-cme-the-implementation-and-outcomes-imperative-for-continuing-medical-education-in-the-learning-health-care-enterprise/

- Teamwork in Healthcare: Key Discoveries Enabling Safer, High-Quality Care (Rosen et al., 2019) https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC6361117/

- The Role and Rise of Interprofessional Continuing Education. (Regnier, Chappell & Travlos, 2019): https://meridian.allenpress.com/jmr/article/105/3/6/431016/The-Role-and-Rise-of-Interprofessional-Continuing

- Twelve Tips for Delivering Successful Interprofessional Case Conferences. (O’Brien et al., 2017). https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/28685632/

- Twelve Tips for Teaching Implicit Bias Recognition and Management. (Gonzalez et al., 2021). https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC8349376/

Facebook

Facebook Twitter

Twitter LinkedIn

LinkedIn Forward

Forward